Scott Alexander pushes again in opposition to the argument that constructing extra housing in a metropolis will cut back housing costs in that metropolis.

He begins by noting that housing prices are usually larger in locations which can be comparatively dense, similar to New York and San Francisco. He’s conscious that this argument is topic to the “reverse causality” subject, which I name “reasoning from a worth change”. Contemplate the graph that he gives:

He’s conscious that the sample above could present an upward sloping provide curve, not an upward sloping demand curve. However he nonetheless means that it’s most likely an upward sloping demand curve, and that constructing extra housing in Oakland would make Oakland a lot extra fascinating that costs really rise, regardless of the better provide of housing. I’ve two issues with this type of argument.

First, I doubt that it’s true. It’s definitely the case that constructing extra housing could make a metropolis extra fascinating, and that this impact could possibly be so sturdy that it overwhelms the value miserable impression of a better amount provided. However research counsel that this isn’t usually the case.

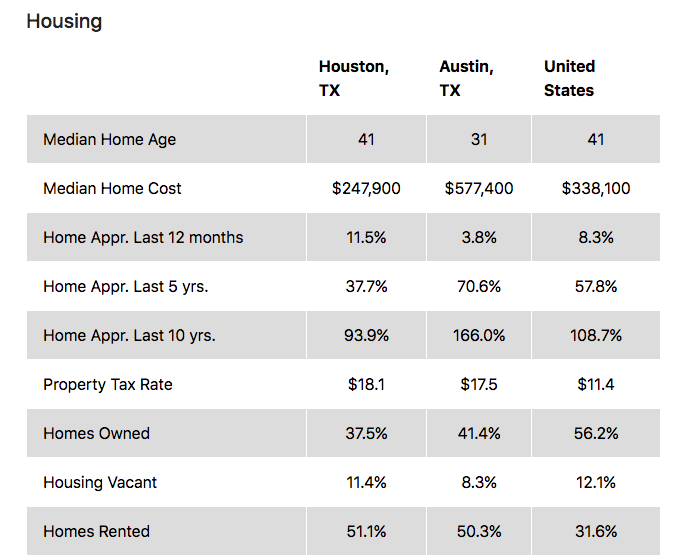

Texas gives a pleasant case examine. Amongst Texas’s large metro areas, Austin has the tightest restrictions on constructing and Houston is essentially the most keen to permit dense infill growth. Although Houston is the bigger metropolis, home costs are far larger in Austin:

Houston just about describes the “Oakland with extra housing” end result that Alexander views as considerably far-fetched. Solely on this case, it’s Austin with extra housing. Alexander appears too fast to simply accept the, “In case you construct it they’ll come” thought—you can construct extra housing and thereby increase demand a lot that costs really rise.

Alexander depends on the next instinct:

Matt Yglesias tries to debunk the declare that constructing extra homes raises native home costs. He presents a number of research displaying that, at the least on the marginal street-by-street stage, this isn’t true.

I’m nervous disagreeing with him, and his research appear good. However I discover in search of tiny results on the margin much less convincing than in search of gigantic results on the tails. If you try this, he has to be improper, proper?

Right here’s the issue with this argument. It mixes up inhabitants change attributable to financial results similar to the advantages of agglomeration, with inhabitants modifications attributable to regulatory modifications similar to much less strict zoning. In case you have a look at issues this manner, then the stylized info work in opposition to Alexander’s argument. Over the previous 50 years, more and more strict zoning has decreased housing building on large cities like New York and San Francisco. In consequence, their populations have elevated by lower than in cities with much less strict zoning, similar to Houston. If Alexander have been appropriate, then the value hole between the tightly managed cities on the coast and the extra laissez-faire cities of Center America ought to have shrunk over time. As an alternative, the value hole has widened. New York and San Francisco have been at all times costlier than different cites, however with tighter zoning and fewer new building the hole has change into far wider.

Nonetheless, I think that there are at the least just a few circumstances the place Alexander’s argument can be appropriate, particularly within the case the place the brand new housing was luxurious properties that changed slums. As an example, if 100,000 properties within the (poorer) jap half of Washington DC have been changed with 120,000 luxurious townhouses, then costs would possibly rise (attributable to a decrease crime price). However even in that case, I consider Alexander can be drawing the improper conclusion:

And it doesn’t violate legal guidelines of provide and demand; if Oakland constructed extra homes, this might decrease the value of housing in all places besides Oakland: individuals who beforehand deliberate to maneuver to NYC or SF would transfer to Oakland as a substitute, decreasing NYC/SF demand (and subsequently costs). The general impact can be that nationwide housing costs would go down, similar to you’ll count on. However the decline can be uneven, and a method it will be uneven can be that housing costs in Oakland would go up.

This isn’t an argument in opposition to YIMBYism. The impact of constructing extra homes in all places can be that costs would go down in all places. However the impact of solely constructing new homes in a single metropolis may not be that costs go down in that metropolis.

It is a coordination drawback: if each metropolis upzones collectively, they will all get decrease home costs, however every metropolis can decrease its personal costs by refusing to cooperate and hoping everybody else does the onerous work. This idea is an effective match for higher-level administration like Gavin Newsom’s gubernatorial interventions in California.

Inform me why I’m improper!

Alexander is implicitly viewing this end result as a “drawback” for town that builds extra housing. They have to sacrifice in order that the remainder of the nation can acquire. However in his state of affairs, Oakland is healthier off. Certainly if it weren’t higher off, then why would extra individuals select to dwell in Oakland? To ensure that it to be true that constructing extra housing boosts housing costs, it should even be true that the standard of current homes (together with neighborhood results) rises by greater than sufficient to offset the rise in provide. Which means the brand new housing building should make Oakland such a fascinating place to dwell that the amenity impact overwhelms the amount impact.

You see the identical fallacy with criticism of freeway enlargement initiatives. Individuals will complain, “They added two extra lanes to the freeway, however the visitors is worse than ever.” However that’s an exquisite consequence! If the visitors is worse than ever, regardless of many extra individuals driving on the freeway because of the further lanes, then the welfare of commuters has elevated for 2 causes. First, extra individuals profit from utilizing the freeway. Second, the truth that they’re keen to make use of it regardless of the next time price implies that they worth the service rather more than earlier than the enlargement. In any other case, the visitors wouldn’t be worse.

After all, financial change at all times has winners and losers. Right here’s how I might describe the impression of permitting extra housing building in Oakland, within the unlikely occasion that this did elevate housing costs:

1. America would profit.

2. Oakland would profit.

3. Poor individuals in America would profit, in combination.

4. Prosperous individuals in America would profit, in combination.

5. Owners in Oakland would profit.

6. Some renters in Oakland would profit (from a extra economically dynamic metropolis.)

7. Some renters in Oakland would undergo from larger rents.

Within the more likely case the place new housing building would decrease costs, the impression described in #5 and #7 would possibly reverse. Both means, there is no such thing as a defensible argument for not constructing extra housing in Oakland, whatever the impression on worth. If constructing extra housing reduces its worth, then there’s a sturdy argument for permitting extra housing building. If constructing extra housing raises its worth, then the argument for extra building is even stronger.