Obtain free Central banks updates

We’ll ship you a myFT Day by day Digest electronic mail rounding up the most recent Central banks information each morning.

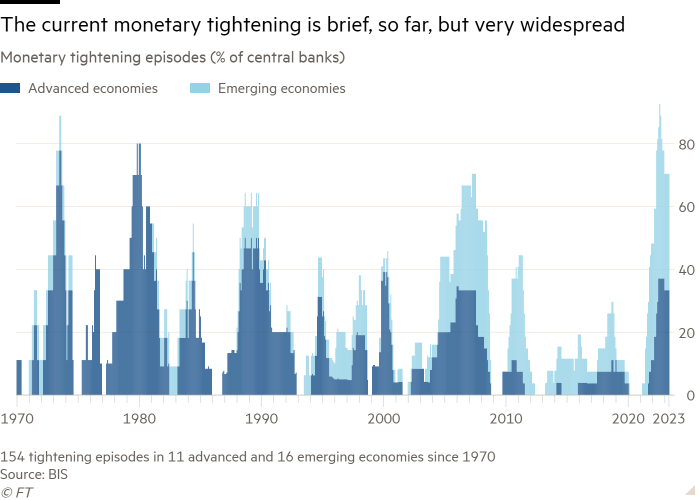

In high-income international locations, client worth inflation is working at charges not seen in 4 many years. With inflation now not low, neither are rates of interest. The period of “low for lengthy” is over, a minimum of for now. So, why did this occur? Will or not it’s an enduring change? What ought to the coverage response be?

Over the previous 20 years, the Financial institution for Worldwide Settlements has supplied a special perspective from these of most different worldwide organisations and main central banks. Specifically, it has confused the hazards of ultra-easy financial coverage, excessive debt and monetary fragility. I’ve agreed with some components of this evaluation and disagreed with others. However its Cassandra-like stance has all the time been value contemplating. This time, too, its Annual Financial Report gives a useful evaluation of the macroeconomic setting.

The report summarises current expertise as “excessive inflation, stunning resilience in financial exercise and the primary indicators of great stress within the monetary system”. It notes the extensively held view that inflation will soften away. In opposition to this, it factors out that the proportion of things within the consumption basket with annual worth rises of greater than 5 per cent has reached over 60 per cent in high-income international locations. It notes, too, that actual wages have fallen considerably on this inflation episode. “It might be unreasonable to count on that wage earners wouldn’t attempt to catch up, not least since labour markets stay very tight,” it asserts. Employees might recoup a few of these losses, with out maintaining inflation up, supplied earnings have been squeezed. In immediately’s resilient economies, nonetheless, a distributional wrestle appears way more possible.

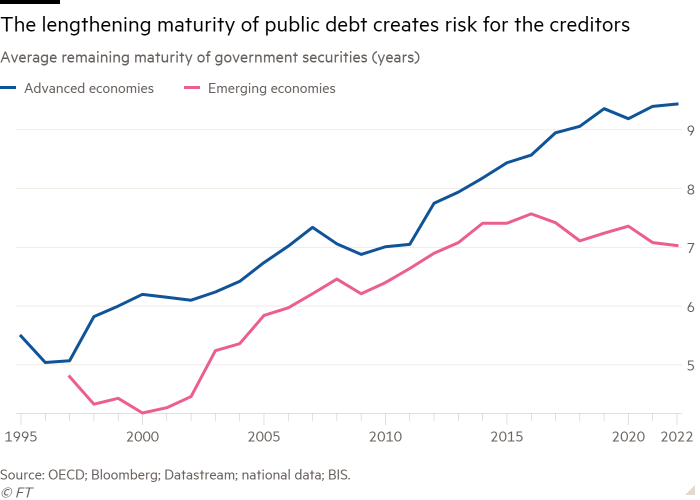

Monetary fragility makes the coverage responses even more durable to calibrate. In response to the Institute of Worldwide Finance, the ratio of worldwide gross debt to GDP was 17 per cent increased in early 2023 than simply earlier than Lehman collapsed in 2008, regardless of the post-Covid declines (helped by inflation). Already rising rates of interest and financial institution runs have prompted disruption. Additional issues are possible, as losses construct up in establishments most uncovered to property, rate of interest and maturity dangers. Over time, too, households are prone to endure from increased borrowing prices. Banks whose fairness costs are beneath guide worth will discover it laborious to lift extra capital. The state of non-bank monetary establishments is even much less clear.

Such a mix of inflationary stress with monetary fragility didn’t exist within the Nineteen Seventies. Partly for that reason, “the final mile” of the disinflationary journey could possibly be the toughest, suggests the BIS. That’s believable, not simply on financial grounds, however on political ones. Naturally, the BIS doesn’t add populism to its checklist of worries. But it surely ought to be on it.

So, how did we get into this mess? Everyone knows concerning the post-Covid provide shocks and the warfare in Ukraine. However, notes the BIS, “the extraordinary financial and monetary stimulus deployed throughout the pandemic, whereas justified on the time as an insurance coverage coverage, seems too massive, too broad and too long-lasting”. I’d agree on this. In the meantime, monetary fragility clearly constructed up over the lengthy interval of low rates of interest. The place I disagree with the BIS is over whether or not “low for lengthy” might have been averted. The Financial institution of Japan tried within the early Nineties and the European Central Financial institution in 2011. Each failed.

Will what we at the moment are experiencing show an everlasting shift within the financial setting or only a momentary one? We simply have no idea. It relies on how far excessive inflation has been simply the product of provide shocks. It relies upon, too, on whether or not societies lengthy unused to inflation determine that bringing it again down is just too painful, as occurred in so many international locations within the Nineteen Seventies. It relies upon, as nicely, on how far the fragmentation of the world financial system has completely lowered elasticities of provide. It relies upon not least on whether or not the period of ultra-low actual rates of interest is over. If it isn’t, this might certainly be a blip. Whether it is, then vital stresses lie forward, as increased actual rates of interest make present ranges of indebtedness laborious to maintain.

Lastly, what’s to be performed? The BIS believes within the old-time faith. It argues that we have now put an excessive amount of belief in fiscal and financial insurance policies and too little in structural ones. Partly consequently, we have now pushed our economies out of what it calls “the area of stability”, through which expectations (not least of inflation) are largely self-stabilising. Its distinction between how individuals behave in low inflation and excessive inflation environments is efficacious. We at the moment are liable to shifting durably from one to the opposite. Developments over the subsequent few years might be decisive. For this reason central banks should be moderately courageous.

But I stay unpersuaded by all tenets of this religion. The BIS argues, for instance, that policymakers ought to have been extra relaxed about persistently low inflation. However that might have considerably elevated the possibilities that financial coverage could be impotent in a extreme recession. It argues, too, that macroeconomic stabilisation just isn’t all that necessary. However extended recessions and excessive inflation are a minimum of equally insupportable. Furthermore, a steady macroeconomic setting is as a minimum useful to development, because it makes planning by enterprise a lot simpler.

Above all, I stay unconvinced that the dominant purpose of financial coverage ought to be monetary stability. How can one argue that economies should be stored completely feeble in an effort to cease the monetary sector from blowing them up? If that’s the hazard, then allow us to goal it immediately. We must always begin by eliminating the tax deductibility of curiosity, growing penalties on individuals who run monetary companies into the bottom and making decision of failed monetary establishments work.

But the BIS all the time raises large points. That is invaluable, even when one doesn’t agree.

Observe Martin Wolf with myFT and on Twitter